by Tetiana Drakokhrust

“By 2050, over 216 million people could be displaced within their countries due to climate change. What happens when they cross borders?”

Climate migration—displacement caused by rising seas, droughts, floods, and other environmental disruptions—is no longer a future threat. It is already reshaping lives, communities, and international policies. The European Union, as a global leader in climate and migration governance, must urgently ask: Is it ready for what’s coming?

Climate Migration: A Growing Phenomenon

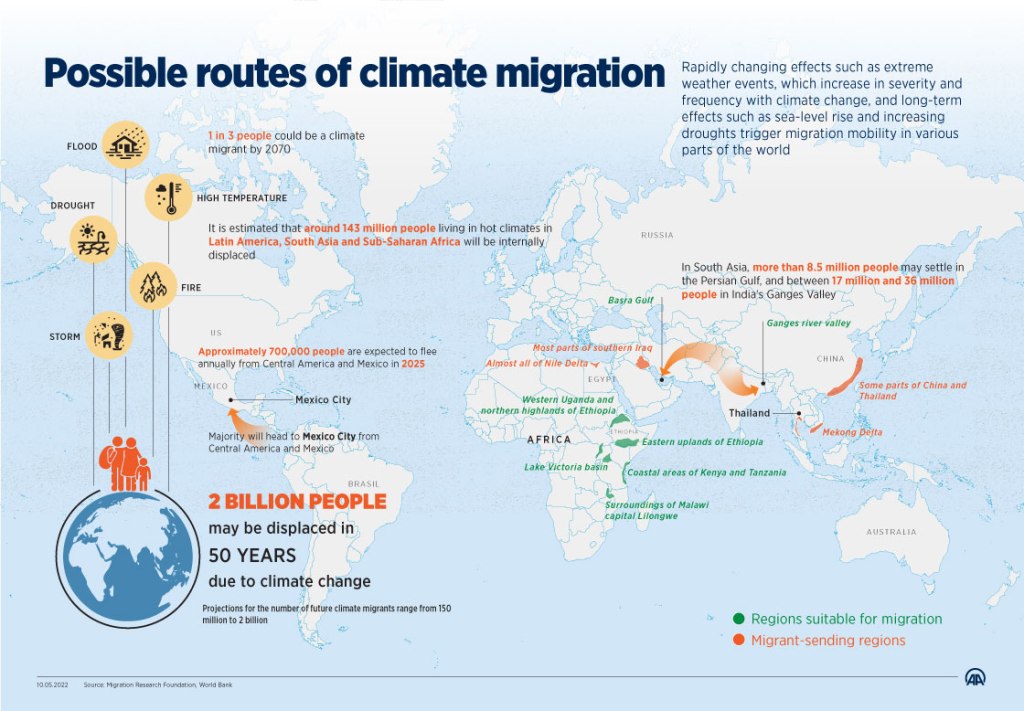

Climate-induced displacement is no longer hypothetical. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), over 32.6 million people were displaced by climate-related disasters in 2022 alone, a trend expected to intensify due to rising sea levels, desertification, water scarcity, and extreme weather events (IDMC, 2023). The World Bank’s Groundswell report estimates that without effective climate and development action, over 216 million people could become internal climate migrants by 2050 (World Bank, 2021). Many of these migrants will eventually cross borders, including into the EU.

While climate change may not be the sole cause of migration, it increasingly acts as a “threat multiplier” exacerbating existing socio-economic and political tensions (UNHCR, 2021). This complex nexus places urgent demands on EU institutions to develop legal, humanitarian, and policy frameworks that address emerging mobility patterns.

Source: https://interactive.carbonbrief.org/climate-migration/index.html

The Legal Gap: Climate Migrants and International Protection

One of the most critical challenges is the absence of a legal status for climate migrants. The 1951 Refugee Convention does not recognize environmental degradation as grounds for refugee protection unless it intersects with persecution (UNHCR, 2021). As a result, individuals displaced by climate-related causes often do not qualify for asylum under EU law.

This legal vacuum leaves many in a state of limbo. While some EU member states have experimented with temporary protection or humanitarian visas, there is no harmonized EU-wide approach. The lack of a coherent framework hinders coordination and limits the EU’s responsiveness (Boas et al., 2019).

Current EU Policies: A Fragmented Approach

The EU has taken early steps to recognize the link between climate change and migration. The European Green Deal (2019) identifies climate-induced displacement as an external policy concern. Additionally, the EU Action Plan on Climate Change and Migration (2020–2024) includes provisions for resilience-building in partner countries (European Commission, 2020).

Yet, the approach remains fragmented. The New Pact on Migration and Asylum (2020) largely omits climate mobility, reflecting political hesitation to redefine protection categories in a sensitive area (European Economic and Social Committee, 2020). The Temporary Protection Directive (2001/55/EC), though designed for mass influxes, has not been adapted to climate contexts and remains underutilized.

Source. https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/a1ec0d1276064ae387c863f2a14b11e1/page/Impacts-on-Migration

Climate Migration and the EU’s External Action

While domestic frameworks lag, the EU has prioritized climate security in its external relations, especially with Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. Programs like the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF) and the Global Climate Change Alliance+ support climate adaptation and disaster risk reduction.

However, critics argue that these policies often reflect a “containment” logic, focusing on keeping migrants out rather than protecting their rights. For example, the EUTF has been criticized for allocating substantial funds to border management, surveillance infrastructure, and return mechanisms rather than enhancing local resilience or mobility rights (Oxfam, 2020).

Source: https://www.statista.com/chart/26117/average-number-of-internal-climate-migrants-by-2050-per-region/

The Need for a Proactive and Inclusive EU Framework

To lead on climate mobility, the EU must adopt a proactive stance:

- Legal Reform. Introduce a formal protection status for climate migrants, potentially as part of the Qualification Directive or by amending the Temporary Protection Directive.

- Policy Integration. Embed climate migration considerations across EU strategies on development, climate adaptation, and asylum.

- Solidarity and Burden-Sharing. Ensure fair distribution of responsibility, as outlined in Article 80 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (TFEU), through relocation schemes and financial support.

- Global Leadership. Support international platforms such as the Platform on Disaster Displacement and the Global Compact for Migration (UN, 2018).

What is “Climate Migrant” Status?

Unlike refugees, climate migrants lack clear legal protection under international or EU law. The 1951 Refugee Convention doesn’t consider environmental threats as valid grounds for asylum—unless they overlap with persecution. Legal scholars and NGOs are pushing for a new framework to close this gap.

Conclusion

Climate migration is an urgent and multifaceted challenge that transcends traditional categories of asylum and economic migration. While the EU has started acknowledging the climate-mobility nexus, its existing responses are inadequate.

To be prepared, the EU must evolve beyond fragmented, externally focused strategies toward a unified, rights-based framework that recognizes and protects climate migrants. This shift will require political courage, legal innovation, and unwavering commitment to human dignity.

But will the Union rise to the challenge—or allow policy inertia and political hesitation to define its legacy on climate justice?

References

Betts, A., & Collier, P. (2017). Refuge: Transforming a Broken Refugee System. Penguin Random House, 2018, 268 p.

Boas, I., Farbotko, C., Adams, H., Sterly, H., Bush, S., van der Geest, K., … & Baldwin, A. (2019). Climate migration myths. Nature Climate Change, 9(12), pp. 901–903.

European Commission. (2020). EU Action Plan on Climate Change and Migration 2020–2024. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu

European Economic and Social Committee (EESC). (2020, November 30). New EU Pact on Migration and Asylum: a missed opportunity for a much-needed fresh start. Retrieved from https://www.eesc.europa.eu/en/news-media/news/new-eu-pact-migration-and-asylum-missed-opportunity-much-needed-fresh-start

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). (2023). Global Report on Internal Displacement 2023. Retrieved from https://www.internal-displacement.org

UN. (2018). Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration. Retrieved from https://refugeesmigrants.un.org

UNHCR. (2021). Legal considerations regarding claims for international protection made in the context of the adverse effects of climate change and disasters. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org

World Bank. (2021). Groundswell Part 2: Acting on Internal Climate Migration. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org

Oxfam. (2020). EU aid increasingly used to curb migration. Retrieved from https://www.oxfam.org.uk/mc/kj7b4g/

Tetiana Drakhohrust is a Doctor of Law, Associate Professor, and Professor at the Department of Theory of Law and Constitutionalism at the Faculty of Law, West Ukrainian National University (Ternopil, Ukraine). She serves as the coordinator of international cooperation at the university’s International Security and Cooperation Center and is the Co-Chair of the Ukrainian Hub of the European Law Institute (Vienna, Austria). She is also the founder of the NGO “EDUCATIONAL START,” Head of the Ukrainian Bar Association Branch in the Ternopil Region, and an Academician of the Academy of Political and Legal Sciences of Ukraine. Her main areas of expertise include Migration Law, Constitutionalism, and Public International Law. She is the author of numerous scholarly works focused on the development of legal systems, the protection of human rights, and the enhancement of legislative mechanisms.

Leave a comment