by Iva Jelušić

“The soul wants rest, and the heart wants joy” (Božović 1984, 194). This is how Saša Božović summed up her thoughts about the summer day of 1943 which included a sports competition, and an evening with “merriment and a theater program.” (Ibid) The sports competition between the several Partisan military units was well attended and accompanied by such loud cheering “that everything reverberated,” (Ibid), and the dinner was set early so that everyone had enough time to dress up for the evening gathering. The performance on the stage, as was customary at similar events throughout Yugoslavia during the Second World War, was continued with an after-party. “Wide, Partisan circle (dance), (which) enveloped the entire field” (Ibid) was, as per usual, the main part of this event. At the very end of the evening, the author, then the leading medical officer of the Second Proletarian Division, did not disturb the wounded and sick of “her” hospital with an evening check-up that would have meant that it was time for the patients to go to sleep. She let them repeat the songs and jokes to each other, to jest and giggle, to savor the joy. She fell asleep, she writes, before them. (Ibid, 195).

Saša Božović was an expert on writing about the everydayness of war. Her first book of memories in which the above-described event was recorded, overflows with scenes from the everyday life of soldiers and civilians who participated in the People’s Liberation Struggle on the territories of Yugoslavia during the Second World War (1941-1945). As she explained in an interview, “(…) (an archival) document is just an old record of an event, just a skeleton of an event from which one cannot read how much a certain, specific, event shook a person or several people, how much they were in pain and anxious.” (Čudina 1979, 14) She clarified that “[t]here are no feelings in the document, not (…) those feelings that I had, that I still have.” (Ibid) Indeed, official reports, notes, and dispatches as a rule do not try to explain when and why someone was bereaved, distressed, or agitated nor if someone was pleased, joyous, or had fun. Contrary to the logic of official reports, notes, and dispatches, Božović focused her memoirs on the emotions at the foundation of events that could have seemed marginal in the framework of a major military enterprise.

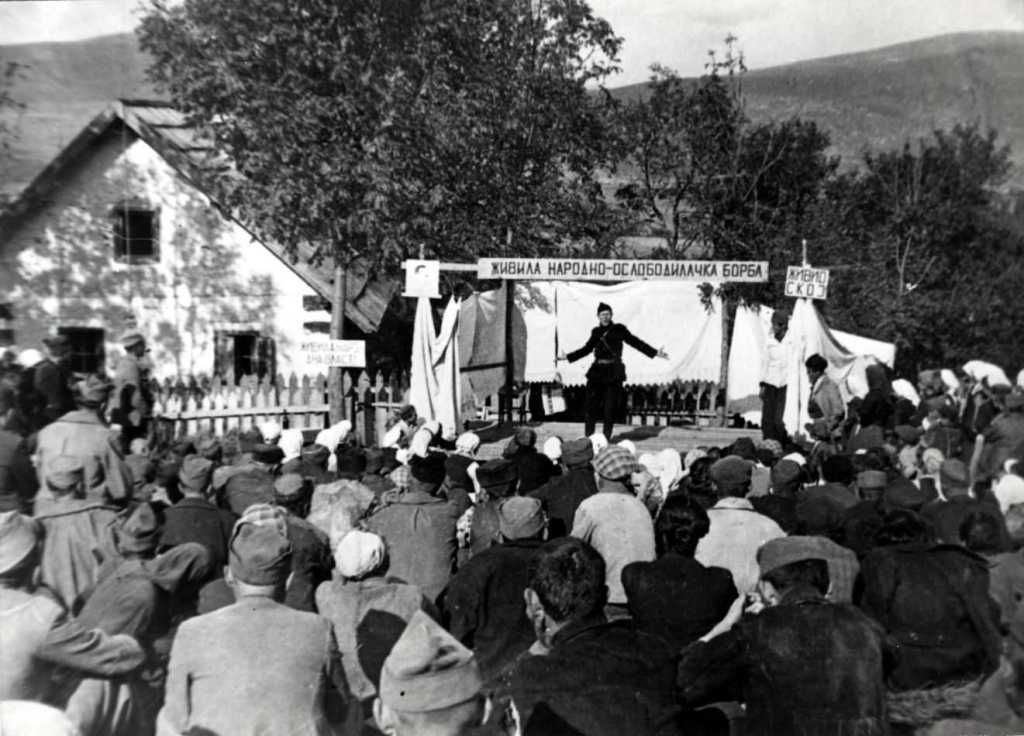

Vjeko Afrić (Theatre of the People’s Liberation)

Source: https://www.muzejavnoj.ba/galerije/kazaliste-narodnog-oslobodenja

In general, researching fun among the Yugoslav Partisans and their supporters during the Second World War, memoir literature proved as the most generous source. There it is possible to find whole paragraphs – although, unfortunately, rarely more than that – describing this or that event that comforted, brightened, and even cheered up those who were present. Yet, excerpts like the described one are relatively rare compared to other content, especially texts focused on military matters such as the development of the Partisan forces into a regular army, the functioning of the army units, conflicts with enemies, and cooperation with the allied units. Moreover, materials about having fun also tend to be scattered and unconnected.

Because of the way remembrances about fun usually appear in sources, in the case of the People’s Liberation Struggle it is best to focus on officially organized entertainment. Although Saša Božović does not mention the specifics – as established, her memoir is not that type of source – the medical staff and patients of “her” hospital, as well as the present Partisan soldiers and locals who wanted to join, during the described evening enjoyed a pre-prepared and rehearsed program based on singing, dancing, and funny skits.

Theatre of People’s Liberation with Tito and his dog. Mlinište (Bosnia-Herzegovina), September 1942.

Source: Davor Konjikušić, Red Glow: Yugoslav Partisan Photography, 1941-1945 (Berlin and Boston: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2021), 57.

Božović does not mention what group of artists performed on the described day. Notably, there were many such groups in Yugoslavia during the war. The first such groups formed both in military units and among civilian supporters, gathered to mark locally relevant occasions. According to Maja Hribar-Ožegović’s foundational research, the people who came together in those ad hoc groups as a rule had little professional experience. However, despite this shortcoming, they attracted large numbers of viewers and managed to interest and mobilize many of them for the goals of the People’s Liberation Struggle (1965, 14). Already during 1942, leadership expectations were formalized through various regulations and based on them (with greater or lesser success) were implemented throughout Yugoslav countries. The most famous and successful in this respect were the Theater of the People’s Liberation (Kazalište narodnog oslobođenja, KNO) and the Slovenian People’s Theater (Slovensko narodno gledališče, SNG), two groups that the theatrologist Aldo Milohnić describes as “two gusts of the merry wind of the Partisan theater.” (2015, 57)

The core of the Theater of the People’s Liberation consisted of seven members of the Zagreb State Theater (the main theater in the Ustasha-led Independent State of Croatia, 1941-1945) who defected to the so-called liberated territory of central Croatia in April 1942. Until the liberation of Belgrade in November 1944, they traveled almost continuously through Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina surviving battles, holding theater performances, educating and entertaining everyone interested. The Slovenian People’s Theater was established in January 1944 and functioned until the autumn of 1945, in this case almost exclusively in the area of the liberated territory of Bela Krajina (southeast Slovenia). Although they may not have traveled and experienced some of the most difficult battles that took place in the Yugoslav theater during this war, as was the case with the KNO’s members, they too worked hard to educate and entertain their audiences.

Finally, as Saša Božović explained in just a few words, and as memoir literature in general, often mentions the importance of the activities of theater groups was that they produced entertainment. Having fun, that is to say, enjoyment in creating art, in participation and collaboration in the process, in the very observation and consumption of artistic products, figured as an important aspect of the work of theatrical groups during the war. Notably, while that was not their only, or even primary, task, participation in performances of the theatrical groups and at the after parties that almost always followed the end of the official program created moments of what Emile Durkheim termed collective effervescence, that is, shared positive emotions leading to a greater degree of social integration, affirmation of common values, as well as the feeling of empowerment (as explained in Fine and Corte 2017, 68-69). This “sunny side of fun” (Ibid, 79) accentuated newly acquired freedom of the utopian (communist) future and allowed the people who moved into the liberated territories to imagine and enact the future that had not yet arrived.

References:

Božović, Saša. Tebi, moja Dolores [To You, My Dolores]. Belgrade: Četvrti jul, 1984 (1979).

Čudina, Marija. “Startov intervju: Saša Božović” [“Start’s Interview: Saša Božović”], Start 277 (September 5, 1979): 12-15.

Fine, Gary Allan and Corte, Ugo. “Group Pleasures: Collaborative Commitments, Shared Narrative, and the Sociology of Fun.” Sociological Theory 35, no. 1 (2017): 64-86.

Hribar-Ožegović, Maja. “Kazališna djelatnost u Jugoslaviji za vrijeme NOB-a” [“Theater Activity in Yugoslavia during the People’s Liberation Struggle”]. PhD diss., Filozofski fakultet u Zagrebu, 1965.

Milohnić, Aldo. “O dveh sunkih veselega vetra partizanskega gledališča in o ‘veliki uganki partizanske scene’” [“About the Two Gusts of the Merry Wind of the Partisan Theater and about the ‘Great Puzzle of the Partisan Scene’”]. Dialogi: revija za kulturo in družbo, 51, no. 1-2 (January-February 2015), special issue: Gledališče upora [Theatre of Rebellion]: 57-76.

Iva Jelušić is a postdoctoral researcher at the “War & Fun: Reconceptualizing Warfare and Its Experience” research project funded by the European Research Council. Her research in this project focuses on the Yugoslav People’s Liberation Struggle (1941-1945), particularly theater production.

Leave a comment